“There are a million ways to do things. You don’t have to be right all the time. You can be in conversation, in dialogue. Ultimately, it can change how you define Art altogether, and I’m excited by that possibility.”

Lisa Jarrett is an artist and educator. She is Associate Professor of Community and Context Arts at Portland State University’s School of Art + Design. She is co-founder and co-director of KSMoCA (Dr MLK Jr School Museum of Contemporary Art) and the Harriet Tubman Middle School Center for Expanded Curatorial Practice in NE Portland, OR, and the artists collective Art 25: Art in the 25th Century.

Her intersectional practice considers the politics of difference within a variety of settings including: schools, landscapes, fictions, racial imaginaries, studios, communities, museums, galleries, walls, mountains, mirrors, floors, rivers, and lenses. She recently discovered that her primary medium is questions.

She is the recipient of a 2018 Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Award, and a 2022 residency at Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at the Barrack Museum of Art in Las Vegas, Russo Lee Gallery in Portland, OR, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and many others.

Lisa Jarrett spoke with Darren Lee Miller via Zoom on Tuesday, September 6, 2022.

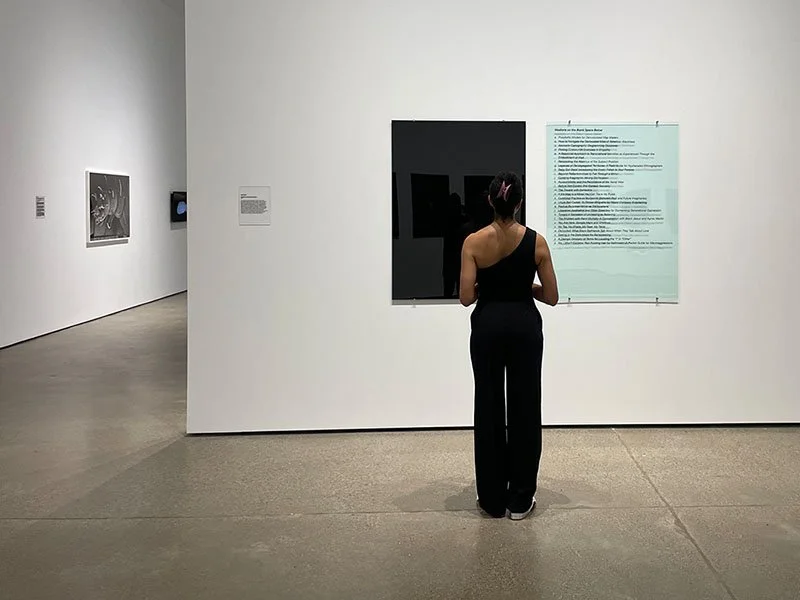

Dee Miller: In your statement you say that the piece we’re showing in the gallery, Meditate on the Blank Space Below, was created as part of Takahiro Yamamoto's performance piece, Direct Path to Detour. Talk a little bit about his project, and then how this piece has taken on a life of its own.

Lisa Jarrett: Taka invited me and a number of other artists to produce works around a performance piece he was building to explore identity in the context of his own practice. So there was a performance and there was also a publication and an exhibition of objects. When I created the piece I knew it would live a double life in a sense. It was going to exist in a publication and on a gallery wall. I conceived of it from the perspective of objecthood, and I approached it without any pictorial information, relying on text. This comes out of being rooted and bound to questions as a central starting place with my work. I ask you to meditate on a space that's below, and that refers to what? What direction is below? Is it straight down? Behind? One panel is transparent with the exception of the text, and the other panel essentially functions like a black mirror. But it's also not a mirror. It just happens that the black space is where you see yourself reflected, even if the didactics of the text are really where people tend to look. Each item in the list is an idea for a ridiculous book title. It was fun to think about how I would use imaginary publications to bring forward ideas about searching for identity, and how identity is put upon us. The piece doesn't give you any real direction. It doesn't give you any answers. I'm more interested in the kinds of questions I end up formulating when I'm trying to work through my ideas.

Miller: It’s interesting that you talked about the blank space possibly being below the reflective, black panel. It’s a really conscious choice to use a black void or a white void, especially when we're talking about subject positionality in these terms. But as you say, the piece is your litany of 26 statements. At first I was looking for blank spaces in between the lines of text, and I thought of them as invitations to reflect and respond. There's a sense of humor but some of them are like, ouch, you know? And then I started to go there and fill in those blanks. It felt like some were targeting arts professionals, like “the trouble with semiotics” while others felt like bias incidents I’ve seen on campus like, “No, I won't fucking cornrow your hair for Halloween.” And then there were these moments of Zen where Black Jesus and Agnes Martin have a conversation. As viewers/readers, are you prompting us to reconsider over simplified notions? Or reflect with some honesty on our past or present blind spots?

Jarrett: It's all of those things. They're funny, they're serious. One of the lines, “Picking Cotton: 100 exercises in empathy” grew into another body of work. And the idea of bias incidents, I want to circle back to that first, because that’s letter Z on the list, right? That's the one that came to me through a student. When she was visiting a friend, the friend’s mother asked her to braid her hair. This friend's mother is a white woman, long story short, she basically had my black student braiding her hair for a Halloween costume! As she told that story I was so mad. I was like, “I wish I had been there with you.” But what would I have said or done? What would you do? What does someone need in that situation? And then there's the one pointing to semiotics and all the things that happen when you start thinking about signs and signifiers. It can be kind of cringy to watch students who are trying to use the things they’re reading to interpret their work at that time, but they’re not quite ready. So there's a place of never being ready for the things we are confronted with. Going back to the notion of the black void versus the white void, when I was conceiving of this object, I was certain it would be on a white wall. I didn’t have to add anything white, the whiteness is always ever present. It's the thing that it's always inside of. And there's the way in which the void of blackness, when combined with reflection, pulls you in because you can't get out of that piece without seeing your shadow or your reflection. I realize there are a lot of ideas contained in this work. That is what happens when I find myself looking for lists to organize the information. How do we put order into our lives? How do we move through the world logically when it is, in many ways, highly illogical? I mean, I’m a person who critiques institutions while also relying on them for my living. We’re in a constant state of paradox and I hope to carry that into the work without diluting it into a simple system of answers.

Miller: Much of your work explores a non-normative or non-majoritarian subject positioning within the American context. You've talked eloquently about the ways in which whiteness maintains its hegemonic position by remaining unnamed and unmarked, so then everything else is “marked/othered.” I imagine your pieces communicate differently to white viewers and viewers of color. What are your approaches to audiencing your work?

Jarrett: It's very much about who can read it, and how. White people speak English, Black people speak English. Many people living in the United States speak English, but it doesn't mean we all understand the same thing when we read a text. I want that to be evident in the kinds of things I have chosen to include in those proposed or imaginary titles without explaining what you might need to know to understand it from the perspective of a Black woman, which is also not a monolithic thing. It's important to avoid speaking in totalities, but I've noticed that when Black people comment on this work, they tell me about one or two lines that really got to them, it just hit home. On the other hand, what typically happens with white viewers is a more somber situation and I’m more likely to hear, “now I know what you’re going through.” And I’m like, “I'm not expecting you to empathize with me like that. I'm suggesting that these could be useful topics.” What I notice mostly is that the emotive content of the conversation based on the identity of the person I'm speaking to is really different. One is like, “Oh, my God, I relate. And here's my story.” And the other is like, “I understand you.”

Miller: So much of your work relies on the audience becoming co-conspirators in the creation of meaning. And it leads me to some of your other pieces like In Equality and People's Homes. It looks like you had a lot of collaborators, so I was curious if you would describe either one of these projects and explain how you coordinate that kind of community participation.

Jarrett: Those two projects are collaborative in different ways. I do have what would be considered a traditional studio based practice where I make objects, although I'm really interested in those being participatory at times. My socially engaged practice is inherently not about the production of an object, but about the sorts of interactions that can potentially happen around an object. The coauthors of People’s Homes, Molly Sherman and Emily Fitzgerald, invited a group of artists to partner with Portland's longtime residents. So each of us partnered with a resident to ultimately produce a kind of yard sign. I wanted to work with oral histories of the 1948 flood that essentially wiped out Vanport, where most of the city’s black population lived at the time. I got to work with Thelma Sylvester to learn about her experience. She was in her early 90s and died less than a year later. It was a beautiful opportunity where somebody else's socially engaged project connected me as a collaborator with somebody else. The art wasn't the sign Thelma and I made – that was just a marker. The point was the relationships and the knowledge that we built together as artists, elders, and community members.

In Equality was a piece for an exhibition called Speaking Volumes, Transforming Hate. It was literally about transforming white supremacist texts. A defecting member from an organization called” The Church of the Creator” had all of these books like, “The White Man's Bible,” and didn't know what to do with them. So he gave them to the Montana Human Rights Network, and they eventually made their way to Holter Museum of Art curator, Katie Knight. She put out a call for artists to physically transform the books. Starting in 2007, I worked with communities of students in the Helena area for this participatory project; and so, most of the kids I've worked with over the years have graduated high school by now. Since I first started that project, I've begun a whole other part of my practice working with young people in Portland. My colleague, Harrell Fletcher and I co-authored and directed a project we call KSMoCA, which is The Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. School Museum of Contemporary Art in a Pre K-5 public school in Northeast Portland. We are building a contemporary art museum inside of a public school, shifting access to contemporary art beyond the primary institutions which tend to be far away, cost money, and don't touch right into the everyday experiences of kids. We want to normalize art.

Miller: It seems like you're literally using pedagogy as a medium. What sort of work has emerged from that?

Jarrett: At the Harriet Tubman Middle School Center for Expanded Curatorial Practice – that's a satellite project to KSMoCA – our original intention was to build a strong contemporary art presence for students that could follow them to middle and high school. What we’ve learned through these partnerships is how valuable it is to work not just with the students, but an entire community of collaborators, administrators, and teachers. At KSMoCA we brought in students from Portland State’s Art and Social Practice MFA program, along with undergraduate students, so that they have an integrated, place-based experience. Meanwhile, the elementary school students remain in their everyday environment. We go to them and enrich that space with the introduction and inclusion of workshops, exhibitions, and works on the walls, and also by building relationships with major contemporary artists who give public talks and lectures. The elementary school students often do introductions for the visiting artists in the school’s library. We're also building an art library that sits within that space, and we have a growing, permanent collection that's been generated over the years. We work in collaboration with the students and the artists. One recent example was our collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas who had an exhibition at KSMoCA at the same time he was showing at the Portland Art Museum. We worked with him to create a photographic quilt made from pictures of every child in the school that included their conclusions to the phrases, “Freedom from…” or “Freedom for…”

Miller: That was part of the For Freedoms project, right?

Jarrett: Yes. The kids got to meet the artist, and they learned to understand his work. They saw it being constructed in real time when we printed and mounted it in the hallway. And then to watch children run up to see their faces and point to the place where they interacted with the artist reminded me of the impact those kinds of experiences can have, especially when we’re young. Those things stick with you. Formative experiences are kernels that carry us through to becoming professional artists. But maybe the best way to say it is there is no single story. It is a cacophony of collaboration, and all the different stories at different levels in different moments in different people, those are the relationships being centered. That’s the Art. The output, as you put it, the things getting made, are a kind of evidence. That artifact is also wonderful, and it’s how an art museum helps the public understand what happened. But none of this is something most of us would expect to see in a K-12 public school environment. We are creating conceptual contrasts, to make these presences and absences more visible.

Miller: It sounds like what you're doing, in addition to everything else, is democratizing Contemporary Art, making it more accessible for those kids, and also empowering them to use their own voices.

Jarrett: Absolutely, but I would replace the word “democratize” maybe with “not-hierarchize,” whatever word that would be, if only because I don't love how political “democratize” is. And when you talk about the broader impact, in a sense the reason it's an art museum is because Harrell Fletcher and I are artists. That's where we come from and how we come to it. The discipline isn't necessarily important, I don't even care if these kids grow up to be artists. I mean, don’t get me wrong, if one of these children walks into my college classroom one day there will be a lot of happy crying. The bigger picture is helping them understand they can have an active role in their education and careers. Most of our students have no idea what it means to be an artist or historian or writer. It's difficult for them to conceptualize. We’re giving kids some of the tools they need to ask a few more questions so they can feel confident approaching things that may even change their minds.

Miller: This idea of empowerment and giving-voice is something I picked up on in your collaboration with Lehua M. Taitano and Jocelyn Kapumealani Ng in Future Ancestors. It felt like a hopeful instantiation of black futurism, or broader than that because it's also indigenous futurism. It made me think of Alicia Wormsley’s ongoing project, There Are Black People in the Future. Can you talk a bit about the experience of working in a space that assumes your lived experiences and realities are normative without needing to be explained? And what was it like to partner with these two women?

Jarrett: Our partnership is ongoing. Lehua and I founded the collective Art25: Art in the 25th Century, to formalize our long-standing artistic collaborations. Then we invited Jocelyn to join us after working with her on Future Ancestors. One thing I've learned in my career is that I can just make it up, and then it's real. Like I made a drawing, we made this collective and now it's here! I say it jokingly, but it is empowering to be able to bring something into being. Lehua and I have been working together informally for years, and we met Jocelyn through a project we did for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, on Oahu. The whole premise of Art25 is that we select an artist somewhere on the globe that we want to work with, invite them to work with us, travel to their location and create art that centers their practice. We focus on how they might understand indigenous futures, Black futures, and the point is getting to know each other so that we can learn collaboratively across great distances. What does it mean to be thinking about Black and indigenous futures in the context of contemporary artistic practice in the 25th century? Obviously we are referencing Art21 – which I think is the best teaching tool of all time – but when I watch those, I still leave with questions. When I was a student watching Art21 I was like, “but how do I even get to be that kind artist when my studio is in a basement?” On the PBS show there's no bridge between emergence and success. We wanted more transparency around things that the art world continues to leave opaque, even when they're supporting the work of artists we admire. Art25 is doing this for me, helping me further my practice as well as meeting the needs of other artists in my community.

Miller: It's a really creative approach to your entrepreneurial practice. I imagine it opens some avenues for funding and additional collaboration.

Jarrett: Exactly. Just claiming collaboration as a modality is important. And I love what happens when you bring people together. There are a million ways to do things. You don't have to be right all the time. You can be in conversation, in dialogue. Ultimately, it can change how you define Art altogether, and I'm excited by that possibility. Collaboration points to something different than a precious object that purports to have been built by one person because, in reality, it takes a lifetime of experiences and the sharing of expertise.

Miller: I believe the building of knowledge is a collaborative endeavor.

Jarrett: I am really excited about the potential for this particular exhibition to point to absences, not just within the canon; but, when you think about what we would want to communicate to another species, when I look at what was included on Voyager, the lens becomes very apparent. Tim Rietenbach said you two were interested in looking through a different lens, and I love the framing of that curatorial perspective. Personally, the word I've been favoring lately is “prism.” Light passes through, and instead of focusing it refracts and you get to see a fuller representation.