Roger Beebe is a filmmaker whose work since 2006 consists primarily of multiple-projector performances and essayistic videos that explore the world of found images and the "found" landscapes of late capitalism. He has screened his films around the globe at such unlikely venues as the CBS Jumbotron in Times Square and McMurdo Station in Antarctica as well as more likely ones including Sundance and the Museum of Modern Art with solo shows at Anthology Film Archives, The Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico City, and Los Angeles Filmforum among many other venues.

His work is included a new exhibition, “1000 Miles Per Hour” at Beeler Gallery at Columbus College of Art & Design (CCAD) that showcases the powers of space and perspective through contemporary photography and lens-based practices. NASA’s Voyager Golden Record and Charles and Ray Eames’ film Powers of Ten are conceptual touch points for this exhibition, as both provide unique perspectives of life on earth through the creative properties of photography and videography. In the words of my co-curator Tim Rietenbach, “This exhibition provides both micro and macro views of Earth. We chose pieces that challenge one’s perspective of how we as human beings interact with space and time—all through the transcendent power of a lens.”

The iteration of Beebe’s “Last Light of a Dying Star” shown in Beeler gallery returns – after 14 years primarily as a multi-projector theatrical performance – to its origins as an installation (originally at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, GA). The installation attempts to recapture some of the strangeness and wonder of space (in a moment where billionaire space tourism has become the norm) while also meta-meditating on the end of the era of 16mm educational films and the decay of the physical material of the film.

“1,000 Miles Per Hour” is part of the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, a monthlong celebration of photography and lens-based art that unites artists, curators, and educators from around the world. The 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, now in its sixth iteration, activates over 100 projects at museums, galleries, universities, and public spaces throughout Greater Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, Dayton, and Columbus, Ohio in October 2022. Each Biennial is structured around a unifying theme; for 2022 that theme, World Record, considers photography’s extensive record of life on earth while exploring humankind’s impact on the natural world. I conducted the following interview with Roger via Zoom on July 21, 2022. The transcript has been edited for concision and accuracy.

Installation view of Roger Beebe’s “Last Light of a Dying Star,” Beeler Gallery, Columbus College of Art & Design, 2022

“I hope it reminds people that space is a wonderful, weird, terrifying, giant, incomprehensible place, and not just another place for us to conduct commerce. I think the Webb telescope images are actually doing that, it’s in the popular imagination right now.”

Dee Miller: You’re just down the road from us at Ohio State University. Did you start there in 2017?

Roger Beebe: 2017 is when we launched the Moving-Image Production Major, but 2014 is when I came into the Art department at OSU. Work on the new major was already underway when I arrived, and what I do is a little different from my colleagues because I typically work in a black box of cinema, rather than the white cube of a gallery. It's been interesting to have more opportunities to exhibit in gallery spaces, and to think differently about temporality and sound with sculptural objects. I've had a lot of support in the department, and there is a community of filmmakers, like Jon Sherman at Kenyon and Jonathan Walley at Denison, and independent filmmakers like Jenny Deller.

Miller: Tell me a little bit about your life before arriving in Columbus in 2014.

Beebe: I took a circuitous path to being an artist, filmmaker, art professor. I was a French major as an undergrad, but I started out as an Economics major. It was my sophomore year abroad in Grenoble, France that changed my mind. I took a lot of theory classes and had an interest in film, but I didn't start making films until later. After graduation I got a fellowship in Paris for a year, so I went back there and worked as a projectionist in a ciné-club. Watching three movies a day made me a sort of autodidact in film. I was applying to grad programs in French, when I had this realization that I didn’t want to teach the subjunctive for the rest of my life, so I decided to go to Duke University’s Graduate Program in Literature because it allowed me a lot of flexibility. In addition to learning critical theory and cultural studies, I started making films. Then I was helping with the Flicker film festival in Chapel Hill, and I eventually started running it. After that, I got a job teaching Film and Media Studies at the University of Florida, where I was located in the English Department. I really liked the context of that department. Students were deeply engaged with theory, reading writers like Walter Benjamin and Laura Mulvey, foundational film theory texts. I also worked a lot with creative writers when I was in Florida, and I love that connection. I remain a big reader of contemporary fiction because it nourishes me in a way that's really important. I just picked up a Yukio Mishima book – the first in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy – in one of those little free libraries in my neighborhood. I allow myself to be promiscuous like that, not always guided by a coherent research project.

Miller: I like that you describe your research practices as promiscuous. What is your ideation process like?

Beebe: Each of my films has been born in really different ways, so I can't say there's one process I follow. I am not always research driven, but when I made a film about Amazon it was deeply research-based. That happened when I hit a point where I was doing my typical observational filmmaking and realized the concept wasn't emerging from the images. So, I fleshed it out with research and it became a different kind of thing, a different process. My concepts rarely precede my encounters with the images and sounds I’m gathering. There's a material investigation that precedes the conceptual, even though my works end up being grounded in the conceptual.

Miller: The film that we're showing in Beeler, “Last Light of a Dying Star” is in large part camera-less. You're working with found material, film strips, didactic films, handwriting, and collage. How did you make the film?

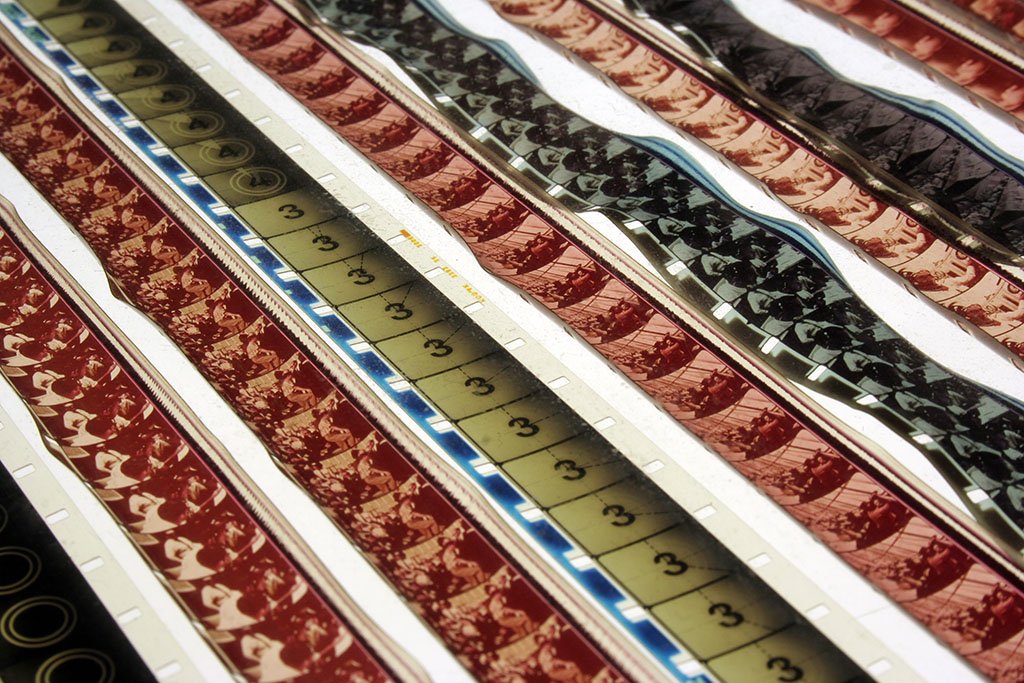

Beebe: It had a very specific origin. I was commissioned to make this work for a show at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon, Georgia. The context of an Arts & Sciences Museum, and an exhibition that centered on outer space, gave me some direction to start thinking and making and finding images. This kind of archival investigation is something I've done more than more than a few times, but this was the first time I did a really deep dive. I had about 4000 educational/industrial films at my fingertips. I only brought about 800 of them when I moved from Florida to Ohio, sadly. A collector in Jacksonville gave me 2000 of them, and the former University of Florida teaching archive held about 1900 film prints that they were going to throw away because they had VHS copies of everything. So I stood between them and the dumpster. Once people knew I was amassing films, they’d just send them to me. In its original form, the film involved both a projected installation and a live performance. The multi-projector piece uses abstractions to suggest things like nebulae and constellations. And when you throw them out of focus, they suggest planets or planetoids. I use animated segments as a kind of pivot to the fully representational images. It's a dual process of me being in the darkroom screwing around with bleach and black-leader to create the abstractions while thinking, how do I get from the abstract to the representational? The first half is in black and white, and the second half is in color, and there's a kind of reset between them. There is also an object that's at the center of the piece in the gallery, made from a Castle Films newsreel called “America on the Moon.” Unfortunately, like many of the prints I have, it has not been treated well over the decades and now it won’t sit flat enough to move through a projector. I was like, how do I give this additional life? And I decided to make a light box piece with it. I'm making new loops that will be triggered by motion sensors for the four-channel piece. And I'll do a performance where I show the theatrical version of “Last Light.” This is an opportunity for me to revisit the sculptural part of it with some new tricks I've picked up over the last eight years.

Detail view of Roger Beebe’s “Last Light of a Dying Star,” Beeler Gallery, Columbus College of Art & Design, 2022

Miller: I'm interested in the multi-modal way the piece will unfold over time in the gallery. It seems like it will be different every time I drop in. And who is Jodie Mack? I noticed that you credited her.

Beebe: Jodie is a former student of mine who's an incredible filmmaker teaching at Dartmouth, conquering the world with her experimental animation. She had a film that was an entry in a competition for Converse. It was a bunch of animated, acetate stars, just a 30-second thing and it didn't win the competition. She didn’t have any more use for it, so I was like, “I love it, I'll take it.” She very generously allowed me to include it in the film. So I cut it in half and made two loops out of it. It's a nice bridge to seeing those didactic films as art too, things that I am transforming, and liberating some of the artistry that is otherwise obscured by their pedagogical contexts.

Miller: This connects to Voyager’s Golden Record, and the idea that the images were somehow going to be literally universally understood. You mentioned the utopian ideals of early space travel in your artist statement and I wondered if you wanted to respond to the connections I’m making before we move on.

Beebe: It seems like an incredible loss that outer space has become a place where we send a billionaire up in a vanity rocket. To do what? I would love to reconnect with what space once meant, a utopian striving of humankind. I occasionally see that sublimity in science fiction films, a desire to encounter the grandness of the universe. I think that there is part of this piece, especially in the sections that deal with abstraction, where I want to have a little bit of that effect. I hope it reminds people that space is a wonderful, weird, terrifying, giant, incomprehensible place, and not just another place for us to conduct commerce. I think the Webb telescope images are actually doing that, it’s in the popular imagination right now. They're lovely images, and we’re told our scientists are learning a lot about outer space from them.

Miller: When I look at your project “de rerum natura,” there's a sense of reverence and optimism on the one hand, and maybe there's a kind of wink to the corniness to some of the imagery. I feel like there's an acknowledgment of the cognitive blind spots that this kind of utopian thinking might create. What I see is like a kind of cautionary tale regarding the hubris and ascendancy of late capitalism. A questioning of the assumption that all of this was inevitable. It shows we have an inability to conceive of what might come next.

Beebe: I would use different words, but you're onto something. I feel anxiety about the sorts of ideologies that subtend our understanding of what is beautiful. I think “Last Light of a Dying Star” is one where I gave myself over a bit to the indulgence of utopian striving, the desire to connect with something bigger; but “de rerum natura” systematically pulls the rug out from under itself. The silent first couple of minutes of the film are juxtaposed with the parts where my voice comes in, suspicious about the things we just saw. I start the film letting you connect with the imagery emotionally, and then I'm like, you shouldn't feel that way. I didn't interject my voice until the third section, but I structured the sequence of sounds to hint that there's going to be something else going other than just, flowers are pretty and nature is good. In terms of its connection to our perceptions about the inevitability of capitalist systems, I did study with Fredric Jameson at Duke and that deeply informs my worldview. I think the failure of the utopian imagination is a serious one. We can more readily imagine aliens coming from outer space to blow up the planet than we can envision changing things through legislative action or a global political movement. That is a founding tenet of my understanding of the world, but it’s not the explicit premise from which these films start.

Miller: I wanted to draw you out a little bit more on the sort of decisions you make in crafting the work. I looked at your 2006 film “S A V E,” and the narration is disconnected from the imagery. Why did you construct and edit the film that way, referring in your narration to images we had seen, but which can't be seen during the moments when you're describing them?

Beebe: A big breakthrough for me as a filmmaker was realizing I didn't have to have sound and image all the time. For example, in music you have rests. I initially thought about having sound in the first section, but I felt like it was obliterating the rhythms emerging from the way it was shot. It's edited in camera, and there's a kind of weird, off kilter beat to it that I had trouble pairing with sounds. In the end I thought, let's allow these image beats to emerge on their own. I wanted to express something more complicated than “I love this place, I love this time of day.” It’s like finding that picture from The Americans that echoed across 50 years, rhapsodically looking but also with a jaundiced eye. So when the talking comes in, it feels like an interesting moment to just listen in the dark. Having a voiceover with no images or not having it be an immediate kind of commentary is a strategy that other filmmakers like Hollis Frampton have used. I have one film with no images at all–I call it a “zero-projector film.” I just love the darkened room and people sitting there, having tacitly agreed that for the next 90 minutes they're going to engage with whatever I put in front of them. If it’s sound, they will listen. If it's images, they'll sit there and look. One of my anxieties about coming into a gallery is that you don't get that “contract,” you get a few seconds of attention if you're lucky.

Miller: Is there a set of creators or filmmakers with whom you identify? Do you see your practice as part of a larger conversation?

Beebe: Jonas Mekas said, “experimental film is a tree with many branches.” One branch I identify with is Stan VanDerBeek’s giant Movie-Drome with every possible kind of projector and lots of disparate images taxing your brain to learn how to make sense of this complex visual field. Anthony McCall's Line Describing a Cone is another film I’m deeply informed by. A lot of these found their way back into galleries through the Whitney Museum's “Into the Light” exhibition about 20 years ago. I'm also really interested in landscape film, so people like James Benning who's still teaching at CalArts. He makes laconic films where, for example, there are 37 shots of trains crossing long shots of western landscapes. Contemporary peers of mine, like Bill Brown and Deborah Stratman, take that language and add a kind of essayistic quality that feels very connected to my way of thinking and making. When I think about the first films that I saw that really pointed a path to me, there's the found footage tradition. Bruce Conner is kind of the father of the found-footage film, even though there were plenty of people making those kinds of films before him. Alan Berliner, who's a generation older than me, made a series of four found-footage films in the mid 80s that were stunning, virtuoso displays of what you can do with the relationship between found images and found sounds. I can go on and on, I feel like I'm handing you a syllabus or something.

Miller: I’m here for it, but one of the things you mentioned was that you were a little nervous about getting back into the gallery space, thinking about viewer engagement with the piece, and time spent with the images. So that made me curious, what do you think is the ideal venue for a piece like this? And how do you envision your audience?

Beebe: I make work that takes advantage of the specificity of that encounter. The challenge is not just, how do I convince spectators to have the experience that I want them to have; but, how do I make work where that can't fail to happen? It's built into the apparatus of the white cube. What does that room do? How do I make stuff for that? There are different answers to that. Sometimes there's a kind of spatial unfolding, and sometimes it's highlighting the sculptural element of the work. The sonic element for this piece involves a certain kind of play, kind of like a puzzle. I hate nothing more than when gallery artists put a two-hour film on a loop in a lit room with quiet sound and somehow expect that anyone will ever sit through the entire thing. Maybe that's not the expectation, but that's not where I'm at. I really want the piece to work in the space, and the space to work for the piece.