According to General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of staff, as of today, the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII in Europe, as many Americans have died from COVID-19 in only eight weeks as were killed on the battlefields of Europe from June - September of 1944 (NPR). Politicians tell us we are fighting an ongoing war against the novel coronavirus, and colleges and universities across the USA are trying to figure out what the fall 2020 semester will be like. We think life on campus is going to be different from anything we’ve experienced. CDC and FEMA models predict that the nation’s barely flattened curve will rise to a new plateau of 3000 daily deaths by the end of June, and a second wave of exponential contagion is predicted for fall (US Department of Homeland Security).

It would be disingenuous to say today, on May 8th, that we know exactly how we will build community, foster inquiry, and deliver our curricula to students when we start classes on August 24th; but, what we really want is for things to “go back to normal.” Our college’s administrators tell us there are three possible scenarios: A - all virtual; B - all face-to-face, but with smaller classes for adequate social distancing and sanitization; and, C - some combination of A and B. While it may not be as satisfying as having a more definitive plan, such is our new global reality, at least until there is an effective vaccine or treatment (2).

Columbus College of Art & Design’s shift to distance learning was nimble and creative, but I think we all agree the move to teaching and learning from home was so sudden that no one had the luxury of time to extensively research how to do it. In the long-term none of us want to move our courses permanently online, but in the near-term we need to be able to do it well. I’m proud to be working with a team of twelve staff and faculty colleagues as part of the college’s first Online Learning Taskforce. Our goals are to research and undertake training in emerging best practices in online art & design education, explore resources for remote course delivery, and curate and present training materials to our colleagues. We are tasked to serve as key points of dissemination and support, and we will test everything before roll-out at the start of the fall semester. I feel lucky that my employer is giving us the tools to think ahead and prepare as well as we can.

As part of our task force training, we are taking online college courses. The goal is not just for us to learn course material, but also to gain a sense of what it feels like to be a student in an online environment. By being on the other side of the desk, we live through the good and bad lectures, the cool videos, the fun interactives, the backlit decapitated talking necks, the intuitive platforms, the frustrating glitches, the exciting and boring demonstrations. Based on our experiences and the material we learn, we will make decisions -- about what is best suited to our teaching styles, our campus culture, and our curricula -- that are informed by experience and colored with empathy. In addition to a graduate course on developing online pedagogy, I’m taking Advanced Adobe Photoshop and Studio Art Photography. The last class is a hybrid digital/darkroom course, and while it is intended for high school art teachers who may want to introduce a photography program to their school, our first homework assignment is compelling me to write this blogpost. The prompt is to choose a moment from the history of photography (we were presented with a timeline of events) and spend this week learning more about it. At CCAD, we assign a similar research project in our foundation photo class. I’m exploring the Autochrome process.

Autochrome was invented by Louis and Auguste Lumiére in 1905 and patented in 1907, about a decade after the brothers invented motion pictures. Preparation of the positive image starts with dying tiny particles of potato starch in one of the three primary colors of light (Red, Green, and Blue), and then mixing the dyed particles so that all three colors are evenly distributed when spread with sticky varnish onto a glass plate. Next, minuscule gaps are filled with lamp black (very fine soot), and then, finally, the plate is coated with photosensitive emulsion. The plates are exposed in-camera with the emulsion facing away from the lens so that the light will pass through a series of filters before activating the emulsion. Or maybe the layer(s) of colored starch particles are what filter the light before it hits the emulsion, it’s unclear exactly how it works even after reading all the articles cited here. Regardless, the process is slow and technical, requiring long exposures with a large-format camera on a tripod. Autochrome was mostly replaced by Kodak’s versatile and more user-friendly Kodachrome roll films in the 1930s, but Autochrome sheet film was still being sold until the mid-1950s.

The relatively large grains of dyed starch, together with the light-sensitive emulsion make a dense positive, and it’s easiest to see the image clearly when the plate is held in front of a bright light. For three decades it was the leading method used for capturing documentary fieldwork in color, never mind that long exposures suggest that subjects either needed to be inanimate or posed and held still. Even so, the painterly photographs reveal the fascinating, beautiful world of one century ago. Since the vast majority of photographic images from the turn of the 19th century are monochromatic (i.e. black & white), I did a double-take when I saw a richly colored image of a winding street near the center of Paris, presumably photographed sometime before the completion of Haussmann’s renovations in that particular arrondissement. The colors rendered by Autochrome are sometimes subtle, other times vivid, and always a half-step away from reality. Viewed up close, the multicolored starch particles create an impressionistic effect of pointillist, dappled light. In Claire O’Neill’s piece for NPR’s, The Picture Show, she notes, “The image of a young Spanish girl with a fan looks more like a Vermeer painting than a photograph.” And yet, Autochrome was widely deployed by journalists who preferred its objectivity over interpretive interventions like hand-coloring.

Original capture, left, shot with my cellphone. The three iterations to the right show the effects of digital filters.

Much of the look of Autochrome, like most other processes, can be credibly imitated in Photoshop, or with the application of filters on Instagram; but the question is, why do that? What does such a manipulation contribute to the signification of a contemporary digital image? To whom is it meant to communicate? If it’s a commercial photograph, what story does it suggest to entice consumer affiliation-with and desire-of the product or brand? Like the images we share on social media, Autochromes are backlit and seen through glass, so in a way maybe there is an unexpected kinship between the two mediums, even in spite of the different contingencies of digital and traditional photographic objects. I find it interesting that historical processes like Autochrome -- if they survive -- continue to be practiced because of their subjective aesthetic, in contraindication to their perceived utility in their own time. In other words, while so many innovations in photography began as scientific advances, it has been artists who breathe life into them by bending usage, keeping some techniques flourishing beyond their serviceable lifespans in journalism, forensics, and other evidence-gathering vocations. A large repository of the uncanny, century-old photos resides in the National Geographic Archives, and it is worth taking a look.

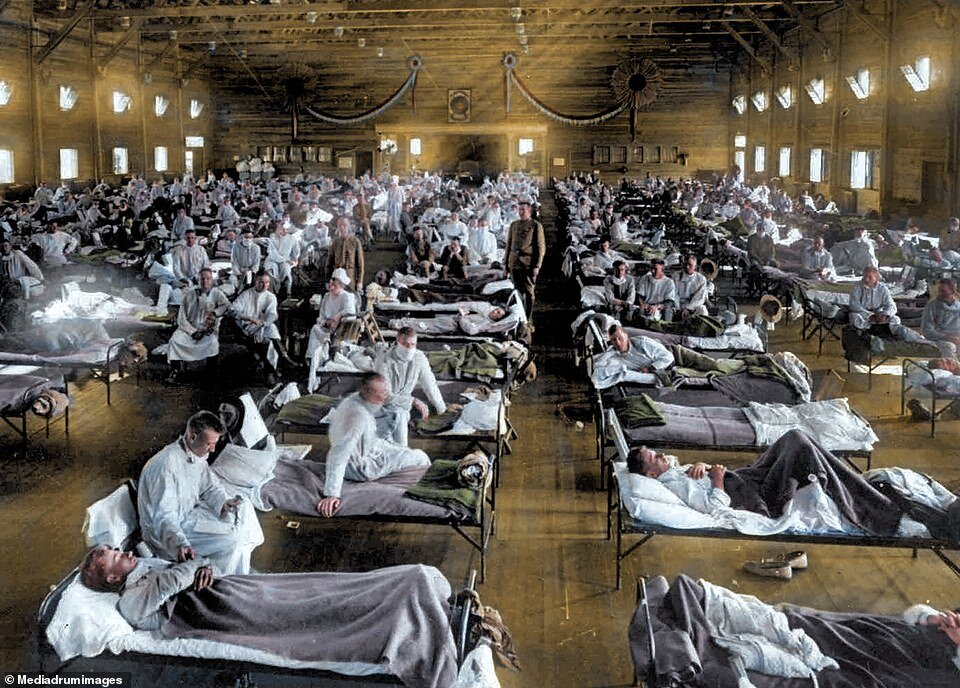

Camp Funston Flu Ward in March 1918. Hand-colored photograph from MailOnline, 16 March 2020. Full citation below.

About one hundred years ago, during the era when Autochrome was most popular, we were emerging from a global flu pandemic that killed more than 50 million people. Surprisingly, I was unable to find Autochrome images documenting that 2-year-long crisis, but I did stumble upon hand-colored photographs (see image from MailOnline). Our school survived the 1918 flu pandemic, and I wonder what we can learn from looking back. Whether we go with option A, B, or C for our fall semester will be decided largely by mandates and recommendations from Ohio’s Governor, Mike DeWine. As social distancing requirements are eased, the need for testing and contact tracing grows; but, a report from Harvard's Global Health Institute shows that Ohio is among 41 states that lack adequate measures to control the spread of infection. The report warns that “without sufficient testing, and the infrastructure in place to trace and isolate contacts, there's a real risk that states — even those with few cases now — will see new large outbreaks (Stein, et al.).” While such political decisions (3) are beyond the purview of our school, I’m excited to be a student again, to help my institution put its best foot forward as we work to ensure that our students' education, health, and safety remain paramount.

Whichever the scenario, these opportunities prepare us to offer guidance to our colleagues and to help our students grow into their full potential. The transition to online learning has shown the benefits and limitations of ZOOM meetings, and has reintroduced many of our students to using the phone for actual talking. In an ideal world I would not supervise projects remotely. I will jump for joy when we can once again safely hug and shake hands and sit shoulder to shoulder, but it’s not all bad. Some online tools I haven’t used before seem to make course content more accessible and increase student engagement. I’ve been impressed by the vulnerable, honest artwork the crisis has already inspired our students to make. Creative deployment of our skills has been an unexpected silver-lining amidst the collateral damage of this pandemic, and I look forward to giving our students what they need to succeed and thrive as we walk forward together -- at a healthy social distance, or maybe remotely -- into our shared, post-pandemic future.

NOTES

The post title is a little play on words, hoping to get this Pointer Sisters earworm stuck in your head because it makes me smile.

Or until at least 50% of the world’s population has been infected to achieve “herd immunity,” which would result in over 300 million people dead.

I find it disheartening that instead of weighing evidence and heeding the advice of epidemiologists, some of our elected officials have used the crisis to create a false equivalency, proclaiming that public health and economic health are at odds with each other.

SOURCES

Andrews, Luke. “Colourised images illustrate how doctors and nurses fought to save Spanish Flu sufferers in 1918... as the world relies on medical heroes to save it from coronavirus a century later,” MailOnline, 16 March 2020. <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8116567/Colourised-images-illustrate-doctors-nurses-fought-save-Spanish-Flu-sufferers-1918.html>

Crowley, Stephen. “Autochrome’s Enduring Allure,” New York Times Lens, 27 May 2010. <https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/05/27/archive-17/>

Gibbens, Sarah. “These 18 Autochrome Photos Will Transport You to Another Era,” National Geographic, 8 April 2017. <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/04/autochrome-photography-archive-vintage-history/>

Hagemann, Hannah. “The 1918 Flu Pandemic Was Brutal, Killing More Than 50 Million People Worldwide,” Special Series, The Coronavirus Crisis, NPR, 2 April 2020. <https://www.npr.org/2020/04/02/826358104/the-1918-flu-pandemic-was-brutal-killing-as-many-as-100-million-people-worldwide>

Nadworny, Elissa. “6 Ways College Might Look Different In The Fall,” All Things Considered, NPR, 5 May 2020. <https://www.npr.org/2020/05/05/848033805/6-ways-college-might-look-different-in-the-fall>

O’Neill, Claire. “Autochromes: The First Flash Of Color,” The Picture Show, Photo Stories from NPR, 26 May 2010. <https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2010/05/25/127112999/autochromes>

“Autochrome,” Paris Photo. <https://www.parisphoto.com/en/Glossary/Autochrome/>

“Top U.S. General On COVID-19, Reorienting For Great Power Competition,” Morning Edition, NPR, 8 May 2020. <https://www.npr.org/2020/05/08/852527722/top-u-s-general-on-covid-19-reorienting-for-great-power-competition>

“History of the Autochrome: The Dawn of Colour Photography,” The National Science and Media Museum. <https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/autochromes-the-dawn-of-colour-photography/>

Stein, Rob; Wroth, Carmel; Hurt, Alyson. “U.S. Coronavirus Testing Still Falls Short. How's Your State Doing?,” Morning Edition, NPR 7 May, 2020. <https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/07/851610771/u-s-coronavirus-testing-still-falls-short-hows-your-state-doing>

Tournassoud, Jean. “Army Scene, 1914,” Artstor, Accessed 7 May 2020. library-artstor-org.cc.opal-libraries.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001701307

“Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Situation Update,” COVID -19HHS/ FEMA Interagency VTC, US Department of Homeland Security, 30 April 2020. <https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6926-mayhhsbriefing/af7319f4a55fd0ce5dc9/optimized/full.pdf?campaign_id=154&emc=edit_cb_20200504&instance_id=18219&nl=coronavirus-briefing®i_id=116357188&segment_id=26609&te=1&user_id=7aed21210059c61effba8d4c0e8a0f34&fbclid=IwAR09OddUiqAx-K7BSqKN06DFq_D2_gskVRhXJX4J8fWehowZLFkt1iI3vbQ#page=1>